Picasso

There are two types of #Picasso biographers, the ones who think he can do no wrong, and the people who think he could do no right.

Pictured above (top left) is Picasso’s well known painting, “Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907”. The middle photo is a preliminary study for one of the woman featured in the first painting. Lauded as the beginning of his radical departure from traditional Western art, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, was one of the earliest paintings to incorporate aspects of Cubism. When Picasso was asked about what inspired his portraits of the two women pictured on the right side of the painting, he answered, “African art? Never heard of it!" (L'art nègre? Connais pas!)

Many Picasso scholars believe that the artist was most certainly influenced by African tribal masks despite the fact that he vehemently denied it into his old age. There is documentation of Picasso closely observing African sculptures and figurines, both in the private collections of his friends as well as France’s deeply problematic ethnographic museums, which continues to parade African art that was stolen from various countries during the height of French imperialism. Picasso is also known to have studied African masks, specifically in an illustrated book by anthropologist, Leo Frobenius. Additionally, many of his contemporaries reported that they had seen African sculptures in his studio. There’s even a photo from 1908, a year after the painting was completed that shows him surrounded by African sculptures. Can we really believe that Picasso had never heard of African art? I truly don’t think so...

We not only have an example of the most blatant form of cultural appropriation, but we can also observe how the myth of the hypersexualized African woman was perpetuated at the turn of the 20th century. Let’s take another look at the first painting 👆🏼, which depicts five women in a brothel staring intently at the viewer. The facial structure of the three women on the left resemble that of sculptures found in the Iberian peninsula, which Picasso was admittedly infatuated with for years. The two figures on the left are noticeably less demure, more animalistic in nature, with one of the figures literally dropping it low.

Considering how the bodies of African girls and women had been exploited for centuries by the time this work was made public (Google Sara Baartman), it would have been well within the cultural norms of Western Europeans to view African women as wild, wanton, and hedonistic, a characterization fully recognized by the tribal references in this work. At least thats how i interpret it. What about you?

Firefox is Celebrating the Weird Wide Web

Love Me The Most

A friend of mine once told me, “it’s alright to think about your ex after you break up, but not about your ex when you’re waiting to have your work reviewed.”

(I have a smart friend. He knows who he is.)

We walk into interviews, meetings, studio visits, dates with boyfriends, and we just want to be loved. Have you ever noticed how much of life is spent wanting the approval of someone else? I mean, why else do people become alcoholics? Because if they’re not going to get it from the person they love, why not through other means?

But I digress….

I remember this one studio visit - spoiler alert - I scheduled it. For some reason whenever I have a studio visit I think that there will be no one else there and that the curator will want to exhibit my art and only my art. I keep this feeling inside me as I go about my days up until they enter my studio. “I’m the only artist they’re considering for this. They just want me. They just want me.” I’ve honestly never admitted this. But what better forum to do so than through a public one, right?

I feel ready, have the paintings prepared, and just feel good. No one else has art that looks like mine, that used the same technique as mine, that jumps out of the canvas in the same way as mine. I’m the only one like me so the rest of you artists can go…

And then they walk in and I see them. 5 other figurative painters who have work that looks like mine, maybe that used the same technique as I, and are all there to discuss the same exact exhibition.

The waves in my long locks deflate a little. The black dress that I thought looked so polished wilts just the slightest. What am I even doing here? Like I have a shot in hell at this...

This.

Is.

Just.

Silly.

I have to talk myself out of these rodent thoughts. They’re not going to help me outside the studio and they’re certainly not going to help me inside the studio. Stop thoughts. Stop. Go. Away.

And as I shake those thoughts away, my name is called. It’s my turn. I breathe deeply, kick my feet a few times (that’s the type of stuff you learn in grad school), and walk near the back wall of the studio where the paintings are hung like a messy jigsaw puzzle.

I’m standing there for a while.

“Less schooled, Jenny. Less schooled. Throw out everything you worked on and just be in the moment.”

And all the while, as I’m trying to be organic in my thoughts and pitching my painting, there’s that little voice that won’t go away. That watches me from up above. How can you be in the moment when you just feel observed from all angles- both inside the studio and outside it?

The longer I talk about my paintings in the studio the more I think they like me.

Like me. Love me. Want me. Need me.

I needed to lose you to love me, yeah ...

To love, love, yeah ... To love, love, yeah.

(Sorry, occasionally I break into a jam when it feels appropriate..)

And look, I don’t care if you’re the most gorgeous, sassiest, self-assured human being on the planet- we have all experienced these emotions (including you). They may be hidden under the “don’t act too desperate” repository, but you can’t help these prevalent thoughts. We just try not to talk about them often. However, I don’t think they make you indigent, I think they make you human. It all depends on how you handle it.

And, yes I booked this studio visit.

After six other visits, I booked the studio visit.

But you would think that after three studio visits they would love my work. But there’s no formula to being loved in the artworld business. Heck, there’s no formula to being loved in any business or relationship.

It can happen after the first date or it can happen after the seventh studio visit.

You just don’t know.

Sincerity & Obvious Fears

“All great truths are obvious truths. But not all obvious truths are great truths.”

“The hardest thing is to be sincere,” young André Gide wrote in his journal in 1890, decades before receiving the Nobel Prize, as he contemplated the central role of sincerity in creative work. But to make sincerity — that amorphous and intangible manifestation of truth and beauty — the measure of artistic success is an aspiration at once enormously courageous and increasingly difficult in a culture fixated on such vacant external metrics as sales and shares.

This paradoxical nature of artistic success is what Aldous Huxley addresses in an essay titled “Sincerity in Art,” found in the altogether magnificent and, lamentably, out-of-print 1960 volume On Art & Artists.

Reflecting on an article by a literary agent who contended to have the key to what makes a bestseller, Huxley winces at how the very question shrinks the creative endeavor:

What are the qualities that cause a book to sell like soap or breakfast food or Ford cars? It is a question the answer to which we should all like to know. Armed with that precious recipe, we should go to the nearest stationer’s shop, buy a hundred sheets of paper for sixpence, blacken them with magical scribbles, and sell them again for six thousand pounds. There is no raw material so richly amenable to treatment as paper. A pound of iron turned into watch springs is worth several hundreds or even thousands of times its original value; but a pound of paper turned into popular literature may be sold at a profit of literally millions per cent. If only we knew the secret of the process by which paper is turned into popular literature!

Amid all this mysterious transmutation by which the human imagination transforms the cheap raw material into priceless works of art, Huxley takes particular issue with the literary agent’s assertion that the sole determinant of the bestseller is that it must be sincere. He digs beneath this unhelpful truism:

All literature, all art, best seller or worst, must be sincere, if it is to be successful… A man cannot successfully be anything but himself… Only a person with a Best Seller mind can write Best Sellers; and only someone with a mind like Shelley’s can writePrometheus Unbound. The deliberate forger has little chance with his contemporaries and none at all with posterity.

But while sincerity in life is a conscious choice — we choose to be sincere or insincere at will — Huxley argues that sincerity in art is a matter of skill that can’t simply be willed:

The truth is that sincerity in art is not an affair of will, of a moral choice between honesty and dishonesty. It is mainly an affair of talent. A man may desire with all his soul to write a sincere, a genuine book and yet lack the talent to do it. In spite of his sincere intentions, the book turns out to be unreal, false, and conventional; the emotions are stagily expressed, the tragedies are pretentious and lying shams and what was meant to be dramatic is badly melodramatic.

In matters of art “being sincere” is synonymous with “possessing the gifts of psychological understanding and expression.”

All human beings feel very much the same emotions; but few know exactly what they feel or can divine the feelings of others. Psychological insight is a special faculty, like the faculty for understanding mathematics or music. And of the few who possess that faculty only two or three in every hundred are born with the talent of expressing their knowledge in artistic form.

Huxley illustrates this point with the most universal experience, love:

Many people — most people, perhaps — have been at one time or another violently in love. But few have known how to analyze their feelings, and fewer still have been able to express them… They feel, they suffer, they are inspired by a sincere emotion; but they cannot write. Stilted, conventional, full of stock phrases and timeworn rhetorical tropes, the average love letter of real life would be condemned, if read in a book, as being in the last degree “insincere.”

The love letter, Huxley argues, is the ultimate testament to the role of talent in so-called artistic sincerity — that, after all, is why the love letters of great writers and artists continue to enchant us with perennial insight into this universal experience. With an eye to Keats’s particularly bewitching love letters, Huxley notes:

We read the love letters of Keats with a passionate interest; they describe in the freshest and most powerful language the torments of a soul that is conscious of every detail of its agony. Their “sincerity” (the fruit of their author’s genius) renders them as interesting, as artistically important as Keats’s poems; more important, even, I sometimes think.

In another essay from the same volume, titled “Art and the Obvious,” Huxley revisits the subject of sincerity from a different angle — our resistance to it, all the more relevant today, amid a culture that wields cynicism like a rubber sword against the perceived weakness of sincerity. He writes:

All great truths are obvious truths. But not all obvious truths are great truths.

Huxley defines great truths as universally significant facts that “refer to fundamental characteristics of human nature” and contrasts them with obvious truths “lacking eternal significance,” like the time it takes to fly from London to Paris, which “might cease to be true without human nature being in the least changed in any of its fundamentals.” He considers the role of each in popular art:

Popular art makes use, at the present time, of both classes of obvious truths — of the little obviousnesses as well as the great. Little obviousnesses fill (at a moderate computation) quite half of the great majority of contemporary novels, stories, and films. The great public derives an extraordinary pleasure from the mere recognition of familiar objects and circumstances. It tends to be somewhat disquieted by works of pure fantasy, whose subject matter is drawn from other worlds than that in which it lives, moves, and has its daily being. Films must have plenty of real Ford cars and genuine policemen and indubitable trains. Novels must contain long descriptions of exactly those rooms, those streets, those restaurants and shops and offices with which the average man and woman are most familiar. Each reader, each member of the audience must be able to say — with what a solid satisfaction! — “Ah, there’s a real Ford, there’s a policeman, that’s a drawing room exactly like the Brown’s drawing room.” Recognizableness is an artistic quality which most people find profoundly thrilling.

But audiences, Huxley argues, are equally voracious for the other, grander class of obviousnesses:

The public at large … also demands the great obvious truths. It demands from the purveyors of art the most definite statements as to the love of mothers for children, the goodness of honesty as a policy, the uplifting effects produced by the picturesque beauties of nature on tourists from large cities, the superiority of marriages of affection to marriages of interest, the brevity of human existence, the beauty of first love, and so forth. It requires a constantly repeated assurance of the validity of these great obvious truths.

The downfall of popular art, Huxley argues, is the inept fusion of these two types of obviousnesses, stripping the former of its uncomplicated rewards of recognizableness and trivializing the latter by bleeding into the banal:

The purveyors of popular art do what is asked of them. They state the great, obvious, unchanging truths of human nature — but state them, alas, in most cases with an emphatic incompetence, which, to the sensitive reader, makes their affirmations exceedingly distasteful and even painful… The sensitive can only wince and avert their faces, blushing with a kind of vicarious shame for the whole of humanity.

In a lamentation at once prophetic and rather ironic amid our era of Hallmark cards and lululemon totes and tea bag fortunes, Huxley adds:

Never in the past have these artistic outrages been so numerous as at present… The spread of education, of leisure, of economic well-being has created an unprecedented demand for popular art. As the number of good artists is always strictly limited, it follows that this demand has been in the main supplied by bad artists. Hence the affirmations of the great obvious truths have been in general incompetent and therefore odious… The breakup of all the old traditions, the mechanization of work and leisure … have had a bad effect on popular taste and popular emotional sensibility… Popular art is composed half of the little obvious truths, stated generally with a careful and painstaking realism, half of the great obvious truths, stated for the most part (since it is very hard to give them satisfactory expression) with an incompetence which makes them seem false and repellent.

With this, Huxley turns to the crux of the tragic denunciation of skilled sincerity that seeded our present era of cynicism:

Some of the most sensitive and self-conscious artists … have become afraid of all obviousness, the great as well as the little. At every period … many artists have been afraid — or, perhaps it would be more accurate to say, have been contemptuous — of the little obvious truths… The excess of popular art has filled them with a terror of the obvious — even of the obvious sublimities and beauties and marvels. Now, about nine tenths of life are made up precisely of the obvious. Which means that there are sensitive modern artists who are compelled, by their disgust and fear, to confine themselves to the exploitation of only a tiny fraction of existence.

In a sentiment of particular poignancy in the context of modern atrocities like BuzzFeed, Huxley adds:

Nor is it only in regard to the subject matter that the writer’s fear of the obvious manifests itself. He has a terror of the obvious in his artistic medium — a terror which leads him to make laborious efforts to destroy the gradually perfected instrument of language… It is extraordinary to what lengths a panic fear can drive its victims.

He concludes with a word of advice to aspiring artists, all the timelier today:

If young artists really desire to offer proof of their courage they should attack the monster of obviousness and try to conquer it, try to reduce it to a state of artistic domestication, not timorously run away from it. For the great obvious truths are there — facts… By pretending that certain things are not there, which in fact are there, much of the most accomplished modern art is condemning itself to incompleteness, to sterility, to premature decrepitude and death.

Pre-vi-sion

Tonight I’m thinking about the world before there were any eyes. What did the world look like before there were eyes? How can one imagine this vision of our planet?

Is this just a paradox? If a tree falls in the forest… bla, bla… It is easy for the paradox to become uninteresting, by merit of its impossibility to answer. So in this hypothetical situation of seeing the world without eyes, who would be looking back? A rock or a person with eyes? I’m interested in the “time machine approach”, how would I see the world if I went back there, when there were no eyes, except mine. I can wrap my head around a blind person’s sense of sight, or a cat’s, or maybe even I can understand the lens a fly looks through, but I can’t wrap my head around the idea of no eyes, ever… To me it seems a question of ontology. How did color come to BE?

Is there a purpose for color when no one is looking? How do you get past the semiotic relationships of color and get to its raw origins? Red means stop, or to Kandinsky the sound of yellow sounds like a violin. In biology a frog is green because he needs to hide. Color theories posit some kind of essential system of color, a system to decode, unlock. These theories are cultural constructs, they are about the way our brains and cultures interpret color.

I am interested in trying to imagine the color of a rock or an ocean or the stars in the sky before the eyes existed to see them. This is a question that reaches beyond any symbolic function with which color is embedded. What were the colors of things when life itself began? Is color simply a matter of chemical composition and the reflection of the sun’s light? Are all the colors the same as they were when eyes evolved? How do astronomers know the color of other planets, and even further out those elements of space that are not visible, but noticeable.

Of course physicists and astronomers have artificial eyes and can read color temperature and wavelength. Does this count as an evolution of the eye? When these mediums and viewpoints become familiar to us we acclimate, like we do to reading glasses.

The first animals with eyes more complex than small pits of photoreceptors connected to nerves where trilobites. At first they could only see light and dark, but their eyes became more complex. Then they lost their eyes when they didn’t need them again, and moved back into climates that didn’t need them. The first eyes to sense light: I think of the Wizard of Oz’s turn to Technicolor, or the idea of a trilobite “Genesis”.

Some scientific theories such as the “Light Switch Theory” by Andrew Parker, assert that one difficult question about evolution can be answered by the impact of evolution of the eye. During the Cambrian period, 540 million years ago, a large number of organisms hopped on the evolutionary fast lane by evolving eyes. The less fortunate ones who didn’t develop eyes became an all-you-can-eat-buffet. The complex eye form then develops and develops to the complex eye that almost every animal has today.

Ultimately our eyes have mutated to be sun-like. They are sun organs, sun receptors, physical mechanisms that are slaves and lovers of light. Since our eyes developed through evolution, we see what the sun can show us, on the earth. We see with the naked eye, red to violet. Perhaps one day our naked eyes will learn how to see other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum like some animals can, or we will live on a place with a slightly different sun and different wavelengths of light. On the infrared end of the spectrum we have radio waves, which give us sound. On the other end of the spectrum are ultraviolet waves and atomic energy. Can we think of these longer and shorter waves as color? Does your microwave or radio make color you can’t see? Or is color forever linked to the visible? According to Wikipedia, the largest wave of electromagnetic energy could be as large as the universe itself. What color is the whole universe?

I can imagine a world without smell, but it is much harder to think of a world where there is simply no such thing as sound or touch, or especially sight. It almost seems like it would be another dimension. What color were things when color wasn’t invented? Waves of electromagnetic energy were moving and radiating and bouncing off surfaces. The primordial soup was being stirred and startled, but there was nobody to witness it, except scientific instruments, measurements and the thoughts of people in the distant, distant future. I can think of this world in terms of energy and mass, or sound, but it is unimaginable for me to think of this place with no senses at all. Perhaps this is why I am not a physicist or a mathematician (and am posing this question in the first place.) Perhaps this is also why the most popular creation myths can be read so literally and pictorially. Our eyes are hardwired into our consciousness.

The way animals have developed visually in response to one another and in response to plants: mimicry, camouflage, attractive coloration. Plants have responded to animals visually too, like the flower. All of these things are so necessary to eyes being; these systems are necessary to eyes having become. There are still fish at the bottom of the ocean that never needed eyes. Still technology is a model for this evolution and coming into being. Descartes and Huygens early lenses looked remarkably like the first real eye lenses that probably developed through evolution. This is an example of biomimetics, or bionics.

I think it is a conceptual exploration to think about color outside of its history, outside of prehistory, when it was a sense without a sense organ, before color had become ‘color’.

Joe

Joe Mack could turn a snail into a student. He could make a bull brilliant. Caught at a desk between bricks and tiered windows I caught glimpses of him in a holy light, steadying his hands and pressing his thick lenses up his nose to focus his energies. He looked like any artist in his mid-eighties should look, with white hair creeping around the back of his skill like ivy, skinny legs held up in suspenders, and checkered button-down shirts that helped his translucent skin glow in every color. Joe presided over Huntington Fine Arts in Huntington, New York. He was the president, minister, bully, and power generator.

When I started at HFA, I felt like a peasant in Joe's kingdom. As a freshman in high school, I learned the process of decision making and action taking, but the process was slow. By the time I became a knight, I had fought in the extended battle against myself to learn to trust my instincts, and I had won. Joe initiated this in me, and it has affected me in all my other areas of work, study, and play. Mistakes do not haunt me after four years of art school. I will summon all the potential in my resources until every difficulty between where I am and where I want to be ceases to be difficult. I will not stop until I express what I intend to express, or come to realize the existence of an ulterior intention that would have been overlooked. Changing directions sometimes makes more sense than following through on the first one. Joe taught me that, too.

The other students and I used to slip our paintings between the closing doors of an elevator that nobody used, and chase them up the two flights of stairs from the plaster-dust, paint-dripped linoleum tiles to the office of pure substance. There Joe would be, ready to talk to each of us personally about where our work was and where it needed to be. He used to say to me, "It's a terrible thing, to be born a creative person. You will know it for the rest of your life." When I would come in clean clothes on weekends to work on a painting, I would see him covered in plaster dust, immersed in something new. "You're dirty," I'd tell him jokingly. "No, you're dirty. I'm working," he would correct me.

The summer before I left for college I worked at the school every day. Some days I would work on internet advertising for the school, sometimes I would design t-shirts or flyers, and sometimes I would have the enormous pleasure of sitting across from Joe in the back corner of the office. He would share stories with me from his archives, vignettes that continually resurfaced, refreshing the outermost realm of his mind. One story I remember most clearly was the one about the single mother and five kids who were all living out of their Cadillac. She found Joe and told him her son was gifted. Joe believed her because, "all of them were." In 1974, he took the kid in and taught him the foundations of studio art. In the 80s he was able to get a job and by the end of that decade, he was a high ranking illustrator at Disney. Joe's cerebral rolodex was always spinning.

When Joe died at the end of 2007 he was still teaching. Friends, colleagues, and students all spoke about the ways in which he sculpted their world. Steve, an old employee of Joe's and the school, told another story from the 1970s about when the school was first starting out. Joe instructed Steve to tear down a wall in the old building, to make room for the drawing studio. Steve protested, claiming the wall was essential to the structural integrity of the building and that it was too big. Joe's response was, "Use a ladder." Metaphorically, he provided that same ladder for me to destroy my preventative walls. My first self portrait sculpture in class was going terribly until I thought I was finally getting it right. I asked Joe to come over and peek at it, and he did. While standing behind him I watched in horror as his muscular, vein-ridden fists punched my soggy grey self. I couldn't believe what was happening. He was severely damaging what I had spent hours working on. Luckily, it didn't take me long to realize that my first crack at it shouldn't have been the best. The first draft never means as much as persistence. The first attack at the problem at hand means nothing until you start over, and trying again is oversimplifying until trying again means one less time that you have to try again before you get what you want out of it. A few weeks later, there I was, ready to create a plaster mold of m first complete self-portrait.

I'll be indebted to him forever, he taught that each student had a voice that would come into its own as soon as it was really listened to. And he was proved right with each student that got the privilege of his ears. Though I have been fortunate enough to have many mentors throughout my life, I love Joe the most because he did it for everyone. He enabled me to continue to mentor myself. He provided opportunities for me that nobody else running a prestigious school would have. He trusted my creative instincts unwaveringly, and through doing so, taught me how to trust my own. He used to come over to my easel, take a look at what I was doing and whisper, "You're brilliant, and I think you might know it."

GODIVA

I spent the afternoon with classmates listening to CEO Jim Goldman talk about their strategy at GODIVA! Can you believe they have an actual ice cream machine in the office?

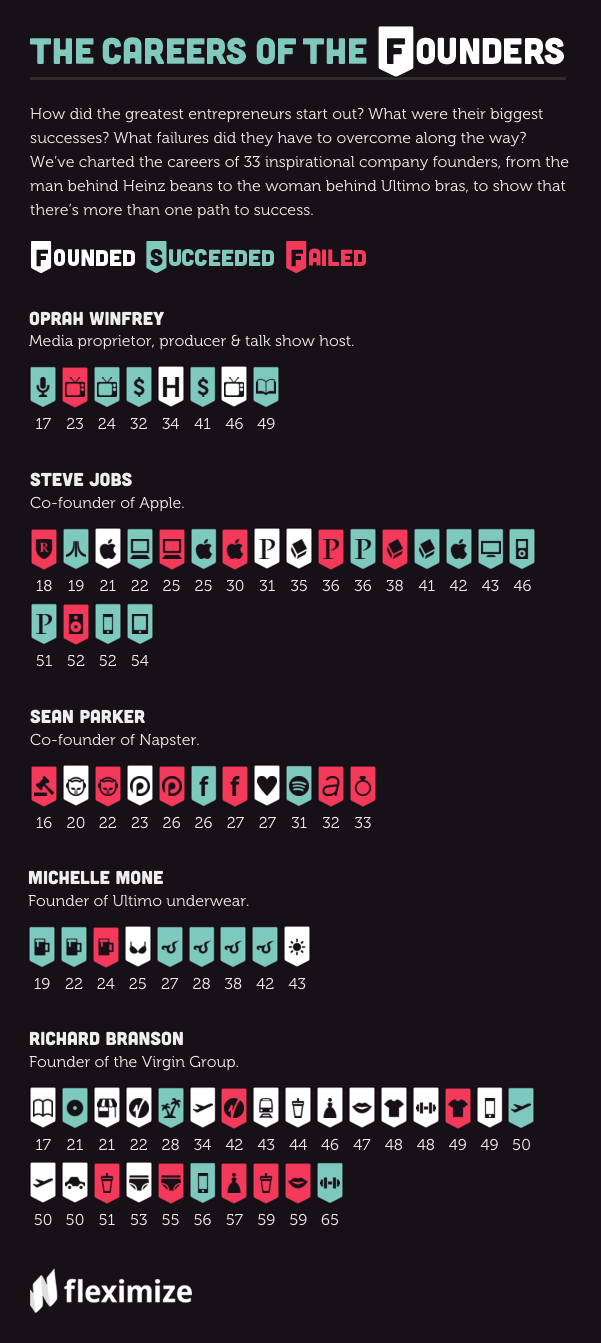

The Careers of the Founders

How did the greatest entrepreneurs start out? What were their biggest successes? What failures did they have to overcome along the way? Fleximize charted the careers of 33 inspirational company founders, from the man behind Heinz beans to the woman behind Ultimo bras, to show that there’s more than one path to success.

Click image to open interactive version (via Fleximize).

HubSpot Certified - Because why not ...

HubSpot Certified

Personal Microculture

William Gibson on Cultivating a “Personal Micro-Culture

Creativity is like a slot machine ...

There’s a certain amount of intuitive thinking that goes into everything. It’s so hard to describe how things happen intuitively. I can describe it as a computer and a slot machine. I have a pile of stuff in my brain, a pile of stuff from all the books I’ve read and all the movies I’ve seen. Every piece of artwork I’ve ever looked at. Every conversation that’s inspired me, every piece of street art I’ve seen along the way. Anything I’ve purchased, rejected, loved, hated. It’s all in there. It’s all on one side of the brain.

And on the other side of the brain is a specific brief that comes from my understanding of the project and says, okay, this solution is made up of A, B, C, and D. And if you pull the handle on the slot machine, they sort of run around in a circle, and what you hope is that those three cherries line up, and the cash comes out.

Collision & Convergence In Truth & Beauty at the Intersection of Science & Spirituality

My objective for a new project is to visually convey the following excerpt from one of Einstein and Tagore’s conversations that dances between science, beauty, consciousness, and philosophy in a masterful meditation on the most fundamental questions of human existence.

EINSTEIN: Do you believe in the Divine as isolated from the world?

TAGORE: Not isolated. The infinite personality of Man comprehends the Universe. There cannot be anything that cannot be subsumed by the human personality, and this proves that the Truth of the Universe is human Truth.

I have taken a scientific fact to explain this — Matter is composed of protons and electrons, with gaps between them; but matter may seem to be solid. Similarly humanity is composed of individuals, yet they have their interconnection of human relationship, which gives living unity to man’s world. The entire universe is linked up with us in a similar manner, it is a human universe. I have pursued this thought through art, literature and the religious consciousness of man.

EINSTEIN: There are two different conceptions about the nature of the universe: (1) The world as a unity dependent on humanity. (2) The world as a reality independent of the human factor.

TAGORE: When our universe is in harmony with Man, the eternal, we know it as Truth, we feel it as beauty.

EINSTEIN: This is the purely human conception of the universe.

TAGORE: There can be no other conception. This world is a human world — the scientific view of it is also that of the scientific man. There is some standard of reason and enjoyment which gives it Truth, the standard of the Eternal Man whose experiences are through our experiences.

EINSTEIN: This is a realization of the human entity.

TAGORE: Yes, one eternal entity. We have to realize it through our emotions and activities. We realized the Supreme Man who has no individual limitations through our limitations. Science is concerned with that which is not confined to individuals; it is the impersonal human world of Truths. Religion realizes these Truths and links them up with our deeper needs; our individual consciousness of Truth gains universal significance. Religion applies values to Truth, and we know this Truth as good through our own harmony with it.

EINSTEIN: Truth, then, or Beauty is not independent of Man?

TAGORE: No.

EINSTEIN: If there would be no human beings any more, the Apollo of Belvedere would no longer be beautiful.

TAGORE: No.

EINSTEIN: I agree with regard to this conception of Beauty, but not with regard to Truth.

TAGORE: Why not? Truth is realized through man.

EINSTEIN: I cannot prove that my conception is right, but that is my religion.

TAGORE: Beauty is in the ideal of perfect harmony which is in the Universal Being; Truth the perfect comprehension of the Universal Mind. We individuals approach it through our own mistakes and blunders, through our accumulated experiences, through our illumined consciousness — how, otherwise, can we know Truth?

EINSTEIN: I cannot prove scientifically that Truth must be conceived as a Truth that is valid independent of humanity; but I believe it firmly. I believe, for instance, that the Pythagorean theorem in geometry states something that is approximately true, independent of the existence of man. Anyway, if there is a reality independent of man, there is also a Truth relative to this reality; and in the same way the negation of the first engenders a negation of the existence of the latter.

TAGORE: Truth, which is one with the Universal Being, must essentially be human, otherwise whatever we individuals realize as true can never be called truth – at least the Truth which is described as scientific and which only can be reached through the process of logic, in other words, by an organ of thoughts which is human. According to Indian Philosophy there is Brahman, the absolute Truth, which cannot be conceived by the isolation of the individual mind or described by words but can only be realized by completely merging the individual in its infinity. But such a Truth cannot belong to Science. The nature of Truth which we are discussing is an appearance – that is to say, what appears to be true to the human mind and therefore is human, and may be called maya or illusion.

EINSTEIN: So according to your conception, which may be the Indian conception, it is not the illusion of the individual, but of humanity as a whole.

TAGORE: The species also belongs to a unity, to humanity. Therefore the entire human mind realizes Truth; the Indian or the European mind meet in a common realization.

EINSTEIN: The word species is used in German for all human beings, as a matter of fact, even the apes and the frogs would belong to it.

TAGORE: In science we go through the discipline of eliminating the personal limitations of our individual minds and thus reach that comprehension of Truth which is in the mind of the Universal Man.

EINSTEIN: The problem begins whether Truth is independent of our consciousness.

TAGORE: What we call truth lies in the rational harmony between the subjective and objective aspects of reality, both of which belong to the super-personal man.

EINSTEIN: Even in our everyday life we feel compelled to ascribe a reality independent of man to the objects we use. We do this to connect the experiences of our senses in a reasonable way. For instance, if nobody is in this house, yet that table remains where it is.

TAGORE: Yes, it remains outside the individual mind, but not the universal mind. The table which I perceive is perceptible by the same kind of consciousness which I possess.

EINSTEIN: If nobody would be in the house the table would exist all the same — but this is already illegitimate from your point of view — because we cannot explain what it means that the table is there, independently of us.

Our natural point of view in regard to the existence of truth apart from humanity cannot be explained or proved, but it is a belief which nobody can lack — no primitive beings even. We attribute to Truth a super-human objectivity; it is indispensable for us, this reality which is independent of our existence and our experience and our mind — though we cannot say what it means.

TAGORE: Science has proved that the table as a solid object is an appearance and therefore that which the human mind perceives as a table would not exist if that mind were naught. At the same time it must be admitted that the fact, that the ultimate physical reality is nothing but a multitude of separate revolving centres of electric force, also belongs to the human mind.

In the apprehension of Truth there is an eternal conflict between the universal human mind and the same mind confined in the individual. The perpetual process of reconciliation is being carried on in our science, philosophy, in our ethics. In any case, if there be any Truth absolutely unrelated to humanity then for us it is absolutely non-existing.

It is not difficult to imagine a mind to which the sequence of things happens not in space but only in time like the sequence of notes in music. For such a mind such conception of reality is akin to the musical reality in which Pythagorean geometry can have no meaning. There is the reality of paper, infinitely different from the reality of literature. For the kind of mind possessed by the moth which eats that paper literature is absolutely non-existent, yet for Man’s mind literature has a greater value of Truth than the paper itself. In a similar manner if there be some Truth which has no sensuous or rational relation to the human mind, it will ever remain as nothing so long as we remain human beings.

EINSTEIN: Then I am more religious than you are!

TAGORE: My religion is in the reconciliation of the Super-personal Man, the universal human spirit, in my own individual being.

- October 2021 (1)

- March 2021 (1)

- January 2020 (2)

- December 2019 (1)

- September 2019 (1)

- August 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- November 2015 (2)

- April 2014 (2)

- March 2014 (3)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (5)

- November 2013 (5)

- October 2013 (2)

- September 2013 (12)

- August 2013 (7)

- July 2013 (5)

- May 2013 (1)

- Barosaurus (1)

- Lambeosaurus (1)

- SEO (1)

- T. Rex (1)

- Web Design (1)

- Web Development (1)

- aquaticreptiles (1)

- art (1)

- bones (1)

- brainpickings (1)

- brainstorm (1)

- branding (1)

- cbs (1)

- chanukah (1)

- collaboration (1)

- creativity (1)

- darwin (1)

- design (1)

- details (1)

- doodles (1)

- drawing (1)

- evolution (1)

- goal (1)

- holidays (1)

- hubspot (1)

- imagination (1)

- infographic (1)

- interior (1)

- lines (1)

- naturalhistory (1)

- paper (1)

- pen (1)

- project (1)

- richardbrautigan (1)

- science (1)

- sherlockholmes (1)

- sketch (1)

- stevejobs (1)

- thanksgiving (1)

- thoughts (1)

- video (1)

- writing (1)

- bobdylan (2)

- goodreads (2)

- quote (5)

The "I" of the Beholder

“The fate of the world depends on the Selves of human beings.”

The Sheltering Sky

The Sheltering Sky, by Paul Bowles, is an incredible story of two people wrestling with (and running from) their freedom, as they rush about between desert towns, chasing a specter as ephemeral as the sand djinn, themselves – their love for each other.

John Lennon

"My role in society, or any artist's or poet's role, is to try and express what we all feel. Not to tell people how to feel. Not as a preacher, not as a leader, but as a reflection of us all." - John Lennon

Collaboration

The history of art abounds with accounts of gifted individuals, solitary creators, and geniuses. There are few modes of human existence that fit the mold of individualism more neatly than the idea of the solo artist lost in the pursuit of their own unique creative vision. From the depths of visionary isolation are brought forth all manner of wondrous objects to be emulated and revered by current and future generations.

Sharify

Easily share data between Browserify modules meant to run on the server and client.

Does Infinity Exist? (unrelated to art)

Infinities in modern physics have become separate from the study of infinities in mathematics. One area in physics where infinities are sometimes predicted to arise is aerodynamics or fluid mechanics. For example, you might have a wave becoming very, very steep and non-linear and then forming a shock. In the equations that describe the shock wave formation some quantities may become infinite. But when this happens you usually assume that it's just a failure of your model. You might have neglected to take account of friction or viscosity and once you include that into your equations the velocity gradient becomes finite — it might still be very steep, but the viscosity smoothes over the infinity in reality. In most areas of science, if you see an infinity, you assume that it's down to an inaccuracy or incompleteness of your model.

In particle physics there has been a much longer-standing and more subtle problem. Quantum electrodynamics is the best theory in the whole of science, its predictions are more accurate than anything else that we know about the Universe. Yet extracting those predictions presented an awkward problem: when you did a calculation to see what you should observe in an experiment you always seemed to get an infinite answer with an extra finite bit added on. If you then subtracted off the infinity, the finite part that you were left with was the prediction you expected to see in the lab. And this always matched experiment fantastically accurately. This process of removing the infinities was called renormalisation. Many famous physicists found it deeply unsatisfactory. They thought it might just be a symptom of a theory that could be improved.

This is why string theory created great excitement in the 1980s and why it suddenly became investigated by a huge number of physicists. It was the first time that particle physicists found a finite theory, a theory which didn't have these infinities popping up. The way it did it was to replace the traditional notion that the most basic entities in the theory (for example photons or electrons) should be point-like objects that move through space and time and so trace out lines in spacetime. Instead, string theory considers the most basic entities to be lines, or little loops, which trace out tubes as they move. When you have two point-like particles moving through space and interacting, it's like two lines hitting one another and forming a sharp corner at the place where they meet.

Symbiosis Between Art and Music

There is a symbiosis between visual art and music. In Manhattan from the 1940s onwards, artists had an empathy for pop music, or its artier manifestations, and vice versa. Jackson Pollock listened to jazz while he painted and Ornette Coleman repaid the compliment by putting a Pollock painting on the cover of his revolutionary recording Free Jazz. No sooner did rock elbow jazz out of American youth culture than artists began to portray Elvis, and by the late 60s, Andy Warhol was bringing together classical modernist music with guttural pop as he managed the Velvet Underground.

Does Art Really Come From Work?

For a while now, conventional wisdom has been criticizing the idea of artistic genius. Forget the Shakespeare who “never blotted a line” and the Keats who wanted poems to come as naturally “as leaves to a tree.” If you want to achieve something great, tack to your mirror that Edison quotation about 99 percent perspiration and 1 percent inspiration; ponder Malcolm Gladwell’s summary of the ten-thousand-hour rule. Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals, a collection of short biographical descriptions of artists’ routines, seems right in step with this trend. It wants to offer a compendium of evidence for the effort-trumps-all theory in creativity studies: “Work work work,” Currey says by way of summarizing his project. This could mark the moment at which art, too, joins our current productivity-mad culture: if you like the Pomodoro Technique and the Fitbit, try the Trollope (he set his watch to write 250 words every fifteen minutes) or the Hemingway (he entered his daily word count on a wall chart). Learn the artistic version of Getting Things Done.

Or, rather, learn how art upends that idea. The accumulation of examples in Daily Rituals, in fact, shows how often artists resist the driven directive to “work work work.” The schedules described are regular, sure, but they’re almost always limited. Most of the artists settle on a timetable that is consistent but abbreviated, with no more than four consecutive hours of creative activity. Some prefer a single stretch, like Thomas Mann’s morning; some, like Simone de Beauvoir, fit in two sessions around a long lunch. Those who spend more time in the office might keep “business hours” but write “for only a small portion of that time”—two hours, in Martin Amis’s case. The maximum, according to Chuck Close, is “three hours in the morning and three hours in the afternoon.” To try for more might be not just difficult but also outright harmful. Ask Descartes, who counted indolence as necessary and “made sure not to overexert himself.” The most prolific figures in the book are not those who worked the longest: Georges Simenon, who published over four hundred books, wrote for only a few hours a day.

This means that writers who took other jobs to pay the bills—Kafka at an insurance office, Orwell at a bookstore—aren’t at much of a disadvantage. An artist’s schedule is important, Currey’s book reminds us, for its refusal to squeeze the most working minutes out of the artist’s waking hours. At a moment when we’re working longer than ever—and, as we dutifully lean in, trying to feel inspired and empowered by working more—it’s useful to recall that many of the greatest minds planned to fritter away parts of their days, that their routines protected creativity by filling the time around a more or less fixed window of possible, genuine intensity. Some strategies are more whimsical, like Patricia Highsmith’s habit of tending snails or Flannery O’Connor’s of raising birds, but most are very ordinary: Stephen King watching baseball, Jean Stafford gardening. There’s a good bit of smoking in this book, and a steady attention to drinking; there’s a lot of walking, too. (It seems to work even if you don’t, like Tchaikovsky, panic at any stroll shorter than two hours.) But one suspects that smoking and drinking and walking are so popular because they are the most universally accessible way to stave off the restlessness of the hours when one cannot—should not—be at a desk. They offer a way to forget how brief and chancy is the ability to create something new, to refine something beautiful, to think something true.

And about that ability, of course, schedules can say very little. That’s another point to be taken from this fascinating compendium. As if to recognize the mystery, Currey’s title evolved, when he turned his blog into this book, from Daily Routines to Daily Rituals. The amendment sneaks something spiritual back into his obsession with habit. Like the rites of religious devotion, the timetables of art surround an essence that is unrepeatable and unquantifiable. “It will appear like a calm existence,” Maira Kalman says of her schedule, but “the turmoil is invisible.” We fetishize that trackable calm because we cannot reproduce the inexplicable turmoil.

So it’s worth remembering that Balanchine was no more able to choreograph Agon because he played solitaire in the morning than Schubert was able to compose the Trout Quintet because he read newspapers in the afternoon or Hobbes able to theorize the social contract because he sang popular tunes in the evenings. If we resist a cause-and-effect logic in our obsession with artistic routines, we can remember that good ideas or great art are the unpredictable outcomes of a predictable regimen—they are, by their very definition, out of the ordinary.